Exposure to high temperatures and humidity is a major challenge for any participant of an endurance running race. Add to this an absence of wind and the invisible enemy, ultraviolet or UV rays, and the runner is faced with a truly fearsome climactic challenge.

During the off-season, many runners plan to race abroad in hostile weather conditions and have to endure thermal shock. A scorching heat wave may also surprise runners during the first spring races when our metabolism is still accustomed to the colder and potentially icy rigours of winter. Are there any strategies to better face this reality?

Biological Mechanisms at Work

The body must be able to shed excess heat caused by the elevation in metabolism. When temperature and humidity are too high, the laws of physics limit the evaporation of sweat, which accumulates on the surface of the skin. There are two options that remain to lower bodily temperature: slow the pace of exertion to reduce the generation of heat, or use cooling methods such as cold water immersion, the application of ice, or hydration.

The optimal temperature for performance in an endurance event is probably between 10 °-12 °Celsius and possibly a bit cooler for faster runners. A 2015 study noted that the performance of athletes in endurance events declines by at least 3% in an environment of more than 25 °C. The effect of heat on the performance of slower runners appears to be more detrimental than that on the performance of elite runners. Is this a question of genetics and talent, or is it a by-product of training?

The ability to sweat is one of the adaptive mechanisms that inhibits a rise in the body’s core temperature. Dehydration therefore has a significant impact on cardiovascular function. It can limit the supply of oxygen to muscle tissues, the intestinal tract and other bodily tissue. A growing body of evidence seems to point to the role of the central nervous system in regulating heat via certain hormones such as dopamine and serotonin. The exact mechanisms are complex and not yet fully understood. What we do know is that when the central temperature rises and sweating reduces circulating blood volume, survival mechanisms are activated. Blood (and thus oxygen) supply will be diverted to « noble » organs such as the heart, the brain and the kidneys. Muscles and intestines will compete for what little is left.

Food and Hydration in the Balance

Can you acclimatize to a hot and humid environment? The answer is not so simple. The success of an endurance race depends on several aspects. Good preparation includes attention to physical fitness, training your gut and psychological confidence.

Experienced runners know very well that they will not eat the same way for a winter event as they would for a summer event. Stomachs trying to operate with a limited supply of blood will be much more erratic in hot, humid weather. It is critical to drink water with each bite, chew your food well and eat smaller amounts more often to avoid developing gastrointestinal distress. It is also suggested to avoid potential irritants such as caffeine and fructose and to favour maltodextrin, as its sweetness is less pronounced and is therefore less likely to cause nausea. The best thing you can do is still to do your homework and test your individual preferences.

There has been a lot of talk lately about managing hydration in hot weather. However, the recommendations remain the same regardless of climate. A sensible increase in hydration will occur in hot, humid weather, but should be guided only by the bodily signal or craving of thirst to avoid overhydration. Moreover, salt supplements have never been shown to be effective in preventing cramps, muscle fatigue or the dreaded hyponatremia.

In terms of physical acclimatization, two 2017 studies, one by Gollan and the other by James, have shown interesting results. It was concluded that the positive effects of heat training dissipate if training is staggered or interrupted. It should also be noted that the positive impact seems to be more pronounced in a dry environment than a humid one and that acclimatization protocols of medium duration (8–14 days) are more effective than protocols of fewer than 7 days.

In Conclusion: Some Advice

If you are planning an event abroad in the winter or spring when your body is adapted to a cold environment, you have two choices: a course of acclimatization ideally lasting more than 8 days with on-site training without interruption, or steady and consistent training in a sauna at home prior to departure.

You also have the option of simply being wiser and more conservative in your race management! Accept the fact that your cardio-circulatory capacity is significantly reduced in heat and adjust your pace accordingly and conservatively.

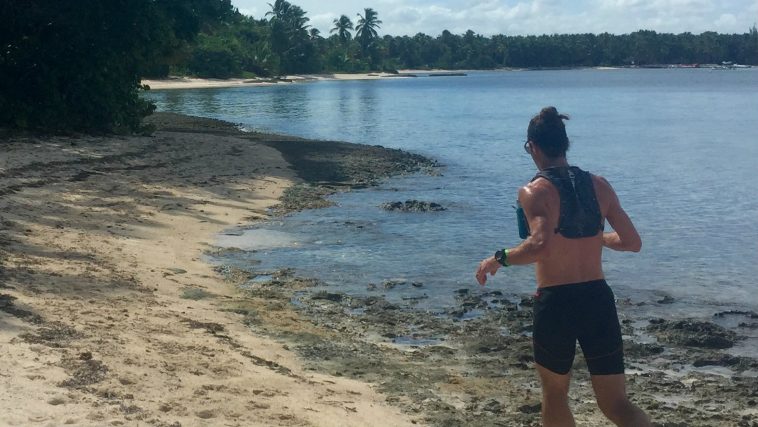

Over a long distance, if you are lucky enough to cross a stream or river, it usually pays to take a few seconds to immerse yourself in the water to lower your bodily temperature. If this break allows you to keep your desired pace, the end result will clearly be to your advantage.

Translation : William Chabot-Labbé

Simon Benoit is an emergency critical care physician, as well as a sports medicine physician. He is a member of the Association québécoise des médecins du sport. He is also a graduate of physiotherapy and chiropractic, and an ambassador for The Running Clinic.

Must Read:

- Feeling depressed or anxious? Try running as a medicine.

- How to choose the best professional to treat an injury

- Becoming a run-commuter, the prescription of Doc Benoit